The Chinese Neuro - Ophthalmological Society 8th Conference

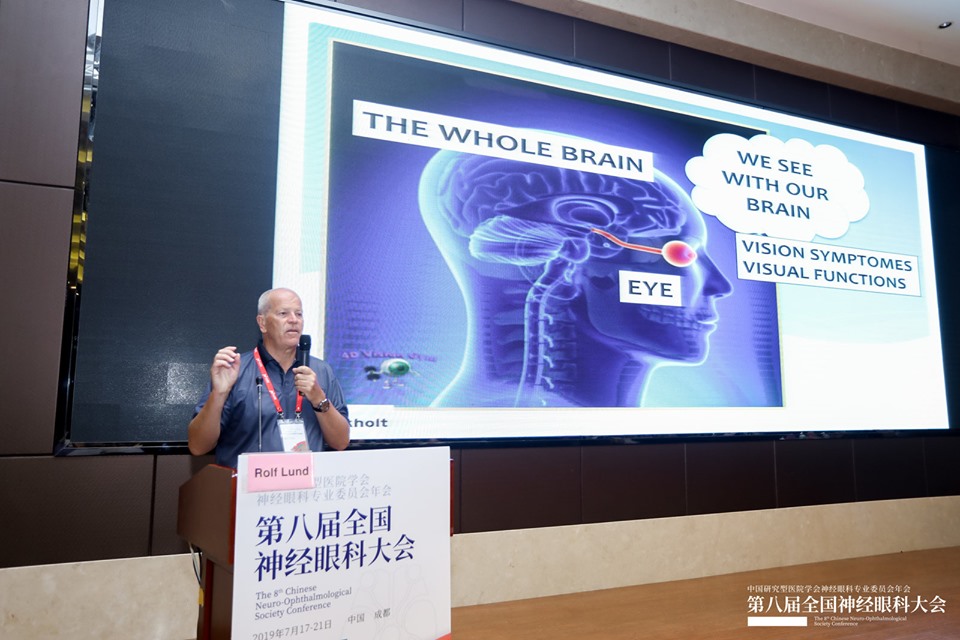

The Chinese Neuro-Ophthalmological Society 8th Conference was held this summer with participation from China, USA and Japan. Invited keynote speaker Rolf Lund from Eikholt, lectured on the role of the brain in the interaction between vision, hearing and balance.

Knowing how the brain utilises the senses - tactile, balance, vision and hearing - is of great importance to those of us working with combined sensory loss.

Researchers studying visual function and brain processes have found that the brain's visual cortex also uses information from the ears when we look at the world. The auditory information supports visual processing. We hypothesise that hearing helps the visual system focus on surprising events and that this has given us a survival advantage. It's also the case that we trust what we see more than what we hear. We hear something and think we know what's going on, but if our vision gives us a different picture, the brain corrects the impression to what we see.

When visual stimuli can be explored both visually and by touch, we learn more effectively and make associations between tactile, auditory and visual stimuli. Part of the reason for this lies in the specific properties of the haptic sense which plays a 'cementing' role between sight and hearing, strengthening the connection between the senses.

Occasionally, we hear people say they've been told that dizziness and unsteadiness come from an inner ear problem, but they feel it has more to do with their eyesight. Is there a connection? The inner ear and the muscles that move your eyes are tightly connected through a reflex called the vestibular-ocular reflex or VOR. This reflex helps us focus clearly when we move our head. This is referred to as gaze stability. As soon as you move your head, the vestibular apparatus in the inner ear registers the exact direction and speed of the movement and tells your brain about it. The brain then uses this information to instruct our eye muscles to counteract the head movement and keep what you're looking at in focus. It's primarily our eyesight that we use to compensate when our balance is off - it happens automatically and without us thinking about it. This means that the visual function in the hearing impaired has two tasks: To compensate for poor balance and impaired hearing.

For people with a combined visual and hearing impairment, the tasks are therefore extra challenging. It really isn't just a case of sight + hearing (1 +1 = 2), it's much more. As a starting point, hearing impairment means that you have to use your vision to read lips and interpret body language. This is a complicated and demanding brain activity that requires concentration and stamina. When the person also has a visual impairment, it becomes even more demanding. With so many tasks, vision and the associated brain networks will be overloaded, so people with combined visual and hearing impairment risk being left with an exhausted body and an overworked brain.